All you need to know about the city of

RACIBÓRZ

Poland

Sightseeing

Visiting Racibórz is like traveling through time—from the Middle Ages to modernity. The historic castle houses interactive exhibitions, while the Racibórz Museum, located in a 14th-century monastery, blends history with a contemporary approach to exhibitions.

curiosities

The town hides mysteries that sound like legends—from a prophecy of the world's end, through the enigmatic Tatar Head, to events that prevented nuclear war.

history

Racibórz is one of the two capitals of Upper Silesia, and its rich history has been intertwined with Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, and Germany over the centuries.

CONTENTS

- The Princess Who Chose the Convent

- The Oldest Graffiti in Poland?

- The Column That Will Destroy the World

- The Mysterious Patron of Racibórz's Chapel

- The Chieftain's Head in the Castle Wall

- An Egyptian Mystery in the Heart of Silesia

- A German Dynasty with the Polish Order

- How a Racibórz Scientist Stopped the German Atomic Bomb

- The Legend of Racibórz's Founding

- The Largest State of Upper Silesia

- The Silesian Fortress That Withstood an Invasion

- The Struggle for the Throne of Racibórz

- Racibórz in Dynastic Chaos

- A State for Rent

- Between Exploitation and Economic Revival

- The City of Three Nations

- The Failed Plebiscite

- The City in Ruins

SIGHTSEEING

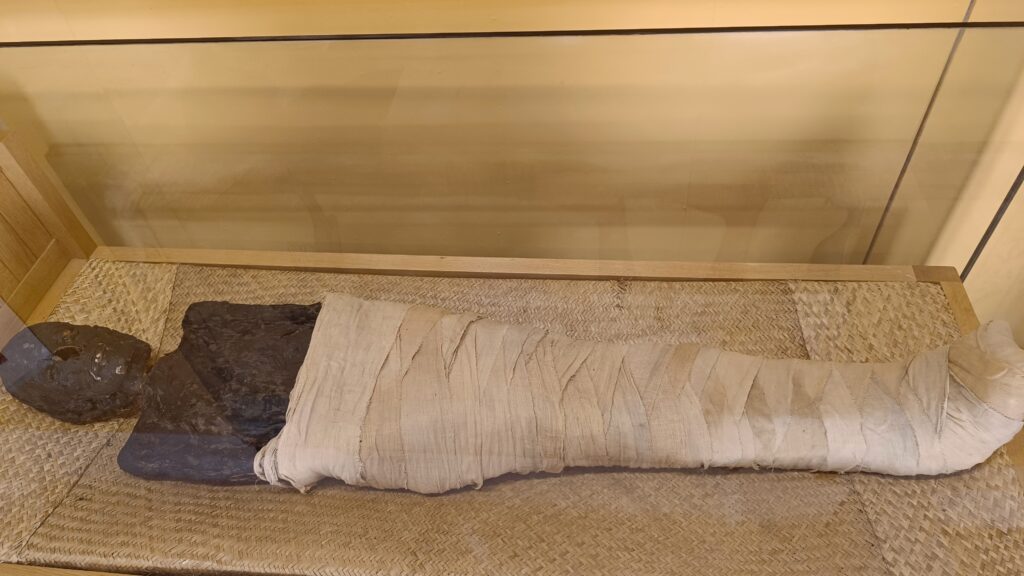

Racibórz Castle

Admission: 40 PLN (regular), 20 PLN (reduced)

The ticket includes a tour of one of the oldest sites in the city. The visit begins with the 13th-century castle chapel of St. Thomas of Canterbury and the castle of the Dukes of Racibórz. Next, the entire group is invited to watch a short film that helps organize the acquired information.

The final stage is a visit to the multimedia museum, where visitors can explore at their own pace. However, guides are always available to answer questions. The museum offers a wealth of knowledge about Racibórz—its rulers, history, and local traditions. It is also an excellent place for younger visitors, featuring games and interactive elements.

Tours take place every full hour and are conducted exclusively with a guide. The entire visit lasts approximately 2 hours.

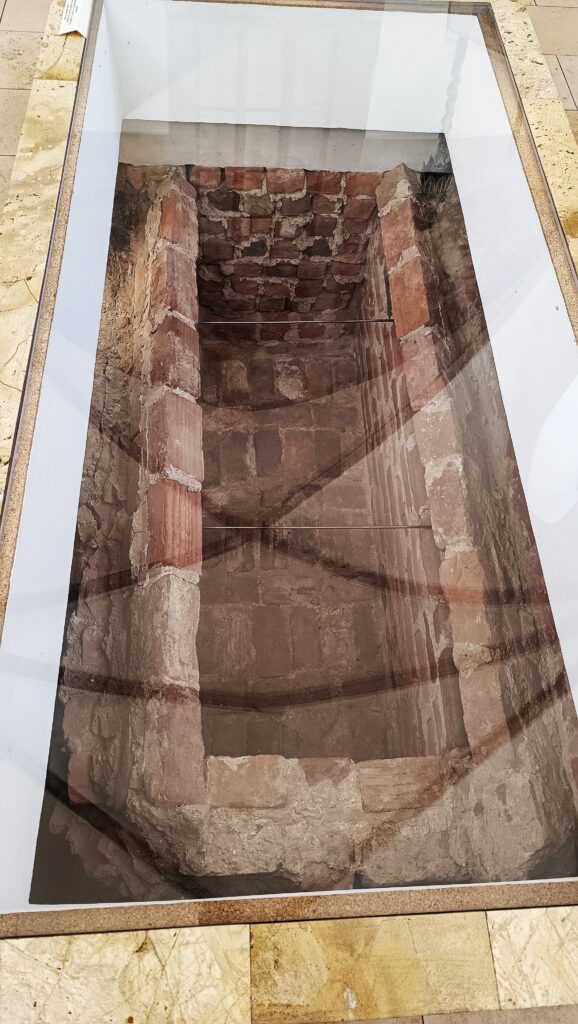

Racibórz Museum

Admission: 15 PLN (regular), 10 PLN (reduced)

The Racibórz Museum is an interesting landmark in the city, worth visiting not only for its history but also for its unique location. It consists of two buildings, one of which is housed in a former 14th-century Dominican convent. There, visitors can delve into the city’s history, see where the Dukes of Racibórz were buried, and view the famous Racibórz mummy.

The second building is slightly less impressive but still offers several fascinating exhibitions. These include a prehistoric exhibit, dental collections, brewing artifacts, and ethnographic displays.

Payment is accepted in cash only.

Market Square and the Marian Column

Admission: Free

The heart of the city is, of course, the market square. It is home not only to restaurants and shops but also to various attractions. Here, visitors can see the monument of Archbishop Józef Gawlina, the 15th-century Dominican church, and the Marian Column, which is said to foretell the end of the world.

St. James Church in Racibórz

Admission: Free

This former Dominican church from the 15th century is the only remaining part of the monastery, which was demolished in the 19th century. The Prussians also intended to tear down the church, but an agreement was reached with the clergy, allowing services to be conducted exclusively in Polish from 1811 onward.

The church underwent reconstruction in the 17th century after a fire. During this renovation, its most remarkable feature was added—the burial chapel of the noble von Gaschin family.

Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Racibórz

Admission: Free

The oldest church in Racibórz and one of the oldest in Upper Silesia, built in 1205. It was rebuilt after a fire in 1300 and redesigned in the Gothic style, specifically in the emerging Silesian Gothic. A notable feature is the 15th-century chapel of Eufemia (Ofka) Piastówna.

Throughout the centuries, the church has endured fires and wars but has always been restored.

Racibórz Castle Brewery

Admission: 30 PLN (regular), 25 PLN (reduced)

The brewing traditions in Racibórz date back to the 13th century. However, the first undisputed mention of the castle brewery comes from 1567. Since then, the brewery has been in operation with only brief interruptions. Over the years, owners and recipes have changed, but after nearly 500 years, the brewery still exists.

Tours are available only on Saturdays and must be booked in advance through the official website of the Racibórz Brewery. A standard ticket also includes a tasting session.

Remnants of the City Walls

Admission: Free

In some parts of Racibórz, visitors can still admire the remains of the 13th-century city walls. Up to 2.5 meters thick and 7 meters high, they were built to protect the city’s inhabitants. In the 17th century, the walls were further reinforced with nine towers, but only one has survived to this day.

Known as the Prison Tower, it once served its original function. Today, after restoration, it has become a fascinating tourist attraction.

CURIOSITIES

The Princess Who Chose the Convent

Eufemia of Racibórz, also known as Ofka, was a 14th-century princess of Racibórz and a Dominican nun. She was considered an exemplary monastic figure. It is said that she knew of her religious calling as early as the age of 12 and consistently rejected all marriage proposals. At times, she served as prioress, overseeing the convent and ensuring the strict observance of Dominican rules, such as vows of silence and the prohibition of eating meals in monastery cells. She was also actively involved in expanding the Dominican order’s wealth.

Ofka is believed to have been a mystic, experiencing visions that deepened her connection with God. She was also credited with miraculous abilities, including healing the terminally ill, alleviating pain, and helping childless couples conceive.

She is regarded as a model of Christian and Dominican values and currently holds the title of Servant of God in the Catholic Church. This means that her beatification process is underway, and she may one day be recognized as a local saint. An official Prayer for the Beatification of Blessed Eufemia has also been created.

Today, in Racibórz, visitors can find Princess Ofka Piastówna Square, located in front of the former Dominican convent.

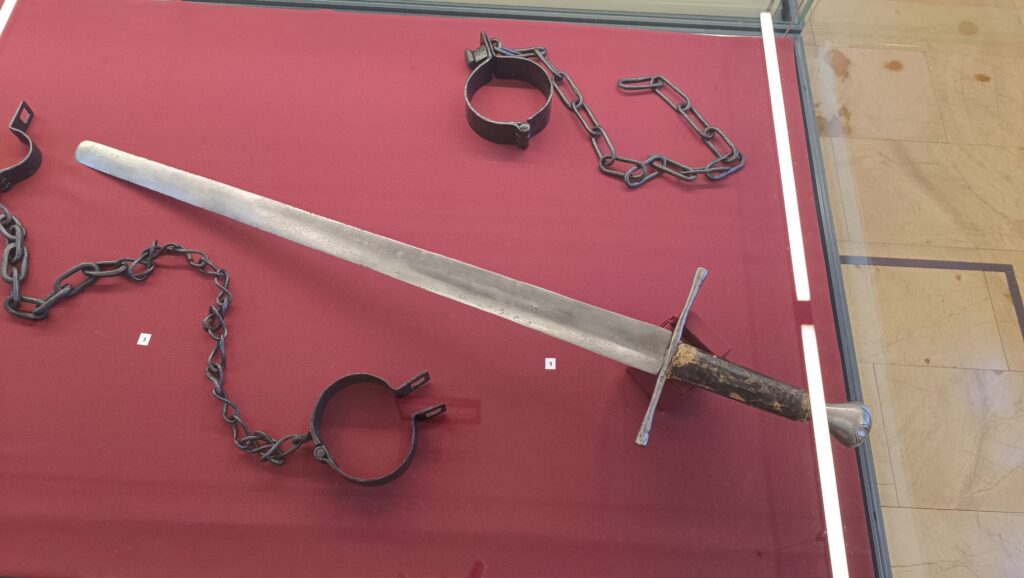

The Oldest Graffiti in Poland?

Racibórz is home to a unique piece of graffiti—unusual because it is over 300 years old. Considered one of the oldest examples of its kind in Poland, it dates back to the 17th century.

The artwork is located in the Piast Castle and was likely created by captured soldiers, as the chamber where it can be found once served as a prison. It is believed to have been made during the Thirty Years’ War, a time when the region saw many prisoners, further supporting this theory.

The Column That Will Destroy the World

Former Habsburg territories are known for their distinctive sculptures—Marian Columns, built as expressions of gratitude for the end of deadly plagues or as protection against future epidemics. Racibórz followed this tradition, erecting its Marian Column in 1727 after a cholera outbreak subsided.

However, this particular column is believed to have extraordinary powers. According to legend, its destruction would signal the imminent end of the world. So far, it has withstood all threats, including WWII bombings, which left 80% of the city center in ruins.

Another legend warns that digging around the column would cause Racibórz to flood. This didn’t stop archaeologists, who conducted excavations near the monument in 1996. Many locals still recall that just a year later, the Oder River’s water levels surged, leading to the catastrophic Millennium Flood.

The Mysterious Patron of Racibórz’s Chapel

Choosing a saint from distant England as the patron of a chapel may seem surprising. However, the decision makes perfect sense when we look back at 13th-century Silesia. At that time, a fierce conflict was raging between Thomas II Zaremba, Bishop of Wrocław, and Henryk IV Probus, Duke of Wrocław.

As bishop, Thomas sought to free the Church from ducal authority, while Henryk aimed to seize Church lands. Their dispute escalated through both secular and ecclesiastical courts. When tensions peaked, Thomas was forced to flee and found refuge in Racibórz, where he consecrated the castle chapel.

Henryk, however, did not relent and laid siege to the city. Though he eventually withdrew, Thomas was forced to submit to the duke. Before that, however, he managed to choose a patron for the chapel—St. Thomas Becket. Like Bishop Thomas, Becket had also defied royal authority and was forced to flee his homeland.

The Chieftain’s Head in the Castle Wall

A Tatar head can be seen in the museum collections of Piast Castle. It is a stone sphere, now heavily eroded. Originally, it was embedded in a castle wall so that everyone entering the courtyard could see it.

In the 13th century, the Mongol invasion of Poland began. The Mongols advanced so successfully that by 1241, they reached Racibórz, seemingly unstoppable. However, at a crucial moment of the siege, the Mongols reportedly saw St. Marcellus appear before them, causing them to panic and flee, leaving behind their dead.

Among the fallen, the Poles identified a Mongol chieftain. As a symbol of victory, they severed his head, sealed it in mortar, and placed it on the castle wall. Following these events, St. Marcellus was declared the patron saint of Racibórz.

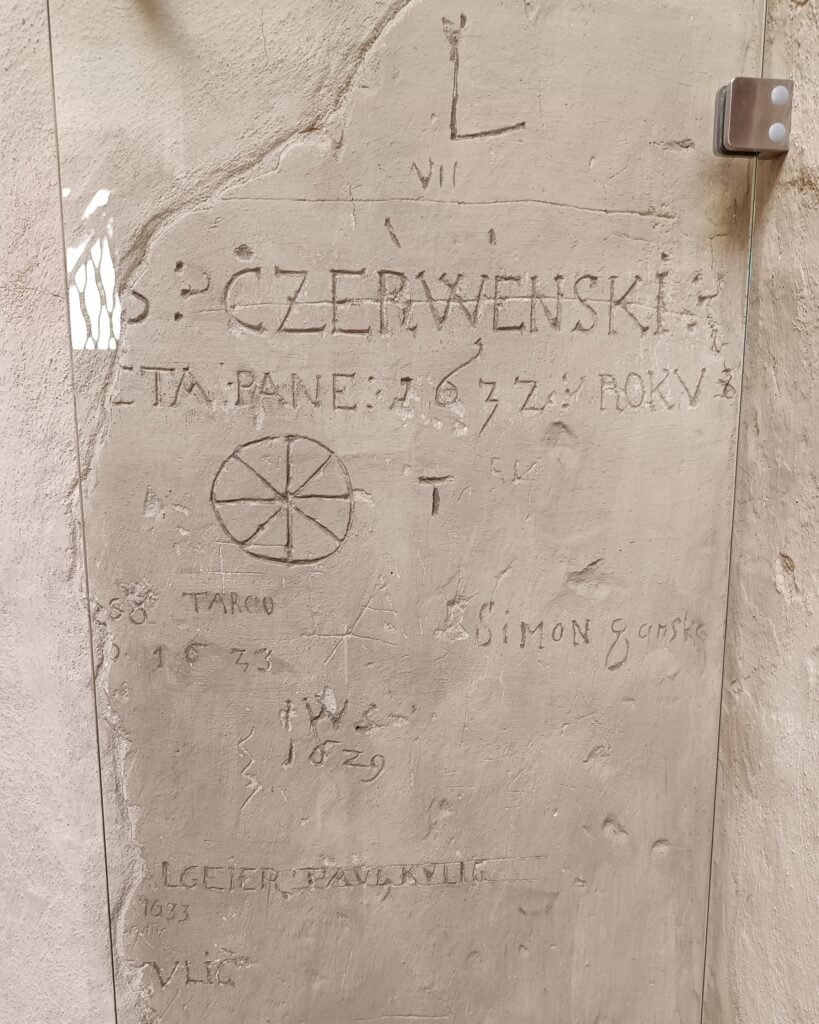

An Egyptian Mystery in the Heart of Silesia

It may come as a surprise, but the Racibórz Museum houses a mummy. It was acquired during a time when Europeans were fascinated by Ancient Egypt. The mummy was purchased by Baron Anselm von Rothschild, reportedly as a wedding gift for his wife.

However, upon seeing the mummy, she was horrified and refused to accept the gift. Unsure what to do with it, the baron decided to donate it to the museum in Racibórz, where it has remained ever since.

A German Dynasty with a Polish Order

Although the era of European monarchies has largely ended, some still hold ceremonial roles. Today, we can find kings in Britain, Sweden, and Spain—and similarly, the Duke of Racibórz still exists. However, he is German. The Duchy of Racibórz was granted to a German noble family in 1821 as the city expanded. Subsequent rulers took on the title von Ratibor.

Why didn’t Poles oppose the title after the Holocaust? The answer lies in the actions of Franz-Albrecht Metternich-Sándor, the duke at the time. From a young age, he was fascinated by Polish culture, visiting Kraków and Poznań before the war. He strongly opposed Nazi policies, which led to his arrest.

After the war, he cooperated with the Polish government-in-exile and supported Racibórz, earning him the Polish Cross of Merit. His pro-Polish stance ensured that his title remained untouched.

Today, his son, Viktor V, continues to hold the title of Duke of Racibórz.

How a Racibórz Scientist Stopped the German Atomic Bomb

It is said that during World War II, the people of Racibórz were not strong supporters of Nazi ideology. One of the most notable opponents was Erwin Schmidt, a local technologist. In 1941, Nazi Germany was attempting to build a nuclear reactor, requiring uranium and deuterium oxide (known as heavy water). However, producing heavy water was a slow process, so the Nazis sought an alternative.

They ordered high-purity graphite from Racibórz, which, in theory, could replace heavy water as a moderator. But Schmidt became suspicious of the strict quality requirements and urgent deadline. Realizing it was likely for weapons development, he intentionally contaminated the graphite.

When German scientists tested the material, they concluded that graphite was unsuitable, and the entire project was abandoned. This act of sabotage became known in history as the Racibórz Diversion.

HISTORY

The Legend of Racibórz’s Founding

In ancient times, a group of hunters set out on a hunt. Among them was a prince named Racibor. At one point, he spotted a majestic deer and, eager to catch it, ran after the animal, unknowingly straying far from his group. Consumed by the chase, he lost track of time, and soon night fell.

The prince called out for his companions, but no one heard him. The forest around him was filled with the sounds of wild animals—bison, aurochs, birds, and possibly even wolves. Terrified, he climbed a tree and began to pray to God, making a solemn vow:

If I survive this night, I will build a fortified town here, where lost hunters and traveling merchants may one day find shelter.

By morning, Racibor was safe and unharmed, and his companions finally found him. True to his word, he fulfilled his promise and built a mighty stronghold, which was named after him. Over time, the name evolved, and today we know it as Racibórz.

The Largest State of Upper Silesia

The first mentions of the Racibórz stronghold date back to the 9th century, when the town was part of Great Moravia. It wasn’t until 1108 that Bolesław III Wrymouth captured the settlement, incorporating it into the Polish state. Soon, the town became a castellan stronghold, increasing in importance. However, Racibórz did not remain within Poland for long. It was Bolesław himself who divided the country into districts, gradually granting each region more autonomy from the central royal authority.

In 1172, Silesia was divided among four Piast rulers. One of the newly created duchies was the Duchy of Racibórz, and its first ruler was Mieszko I Tanglefoot. In 1201, he also took control of Opole, creating the first Opole-Racibórz Duchy, the largest Upper Silesian state in history. Subsequent rulers of the duchy established Racibórz as their most important city, primarily due to its proximity to Kraków.

The Silesian Fortress That Withstood an Invasion

The 13th century was marked primarily by the Mongol invasion of Polish lands. Many towns and villages in Silesia suffered, but Racibórz emerged from the conflict unscathed. In 1241, Mongol forces were repelled twice—an impressive feat, considering that even Kraków fell to the invaders. Following these events, the decision was made to build stone defensive walls, fragments of which can still be seen in Racibórz today.

In 1290, the duchy was divided among the Piast princes. As a result, a smaller Duchy of Racibórz was established—without Opole, Bytom, or Cieszyn.

In 1299, Racibórz was granted city rights under Magdeburg Law, securing trade privileges and the right to host assemblies, which significantly accelerated its development. From this period also comes the Chapel of Saint Thomas Becket, which can still be admired in Racibórz today.

The Struggle for the Throne of Racibórz

In 1306, Leszek took power in Racibórz and sought to maintain close relations not only with the Polish state but also with neighboring Bohemia. His policies led to him paying homage to the Czech king, John of Luxembourg, in 1327. At the time, John was also the Emperor of Germany and one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe.

This homage had far-reaching consequences—just nine years later, Leszek died childless, bringing an end to the Piast dynasty of Racibórz. The Czech king appointed Nicholas II from the Přemyslid dynasty as the new Duke of Racibórz.

This decision outraged the Silesian Piasts, who believed that the Racibórz throne should go to one of their own. However, the Czech king remained firm. King Casimir III of Poland saw an opportunity in the conflict and invaded Racibórz in 1345. Having Racibórz’s roots himself, he hoped to gain the support of the Silesian Piasts and restore them to power. His plan ultimately failed, and Silesia was lost.

Racibórz in Dynastic Chaos

For the next 200 years, Racibórz remained under the rule of the Přemyslid dynasty from neighboring Opava. During this period, Racibórz held a dominant position in Upper Silesia and was one of the most populous Silesian cities.

The Přemyslids were known for their loyalty to the Czech kings. They also maintained good relations with Poland, even supporting Poles in the Battle of Grunwald. The last duke from this dynasty was Valentin of Racibórz, who never married or had children. As a result, he made a survival pact with John II the Good, the Piast duke of Opole. According to this agreement, the duchy would go to whichever of the two outlived the other.

Fate decided that Valentin died first, and in 1521, the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz reappeared on the map. Unfortunately, the Piasts did not rule Racibórz for long. It is said that John II was impotent, which meant he never had children. After his death, many contenders vied for the throne, but the strongest claim belonged to the Austrian Habsburg dynasty, which also ruled Bohemia. However, John II had favored George Hohenzollern and intended to pass power to him. Ultimately, the German and Austrian rulers reached a compromise— the Hohenzollerns were allowed to govern the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz only as a temporary lease for a specified period.

A State for Rent

In 1552, Racibórz came under the rule of the Habsburgs. The city gained new rights, navigation on the Oder River was regulated, and Racibórz became an important river port. In 1567, the Racibórz brewery was mentioned for the first time.

However, at the beginning of the 17th century, the city suffered a wave of destruction due to the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648)—one of the largest and most devastating conflicts in European history. Silesia, caught in the struggle between the Catholic Habsburgs and the Protestant Swedes and Hungarians, suffered massive economic and demographic losses. For a short time, Racibórz was controlled by the Hungarians, but ultimately, the duchy returned to Habsburg rule.

In 1645, the lands of the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz briefly became part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They were given to King Władysław IV Vasa as a pledge—if the Habsburgs failed to buy them back within 50 years, the duchy would become a permanent part of Poland. However, the duchy remained within the Commonwealth for only 20 years.

Between Exploitation and Economic Revival

Frequent changes in rule had disastrous effects on the region. Each new ruler, aware of the temporary nature of their power, sought to exploit the duchy’s resources as much as possible. High taxes were imposed, livestock was confiscated, and residents were conscripted into the military.

A significant historical event for Racibórz occurred in 1683 when the city enthusiastically welcomed King John III Sobieski on his way to relieve Vienna. However, despite his successful campaign, the Habsburg state soon faced a much stronger adversary from the north.

Everything changed in 1742. Following their defeat in the First Silesian War, the Habsburgs were forced to cede almost all of Silesia to the rising Kingdom of Prussia. For Racibórz, this marked the end of the centuries-old duchy as an independent administrative entity. However, it was under Prussian rule that the city experienced a true economic boom. The population grew to 3,000 people, reaching levels comparable to those before the Thirty Years’ War.

The City of Three Nations

At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, Racibórz became home to the second printing house in Silesia and saw the establishment of a high school. In 1821, Racibórz was once again elevated to the status of a duchy, which was taken over by Victor Amadeus. His successors bore the title von Ratibor. The city’s development accelerated further with the construction of railway connections—first to Wrocław and later, in 1848, to Berlin and Vienna. This transformed Racibórz into a major trade hub, enabling the export of local products such as Racibórz beer and chocolate throughout Germany.

By the pre-war period, Racibórz had a population of 40,000. However, the city’s demographic structure did not favor the Polish national movement—about 30% of the inhabitants were Czechs, while the majority were Germans. Despite this, a Polish newspaper, Nowiny Raciborskie, operated in the city, along with organizations that united the Polish community.

The Failed Plebiscite

After World War I, a series of three Silesian uprisings broke out in German-controlled Silesia, aiming to incorporate Upper Silesia into Poland. Part of the Racibórz district was annexed by Czechoslovakia, while a plebiscite was organized in Racibórz itself in 1921. In the vote, only about 9% of residents supported joining Poland, ultimately crushing the hopes of Polish Racibórz’s citizens for the city’s inclusion in the Second Polish Republic.

Following the uprisings, Germany retaliated against the region’s Polish population for their independence efforts. Nowiny Raciborskie was shut down, restrictions were imposed on Polish organizations, and people speaking Polish in public were often harassed. The emergence of independent Poland and Czechoslovakia weakened Racibórz’s significance as a transportation hub. The new national borders severely hindered trade and free travel, negatively impacting the city’s economy.

The City in Ruins

During World War II, Racibórz was an important industrial center, producing, among other things, rockets for the German army. The city housed three labor camps, a harsh prison, and a camp for displaced Poles. In addition to them, French, British, Italian, and Russian prisoners were also held in Racibórz.

Due to its strategic significance, Racibórz became a target of intense bombings. Around 80% of the city center was destroyed, and in 1945, the Red Army captured the city. The post-war reality was devastating—both the industry and population of the city lay in ruins. By the end of the war, only about 3,000 people remained in Racibórz. It was only through the influx of Polish settlers that the city was repopulated, but it did not regain its pre-war population until the late 1970s.

In place of the destroyed historic townhouses, communist-era apartment blocks were built, while some construction materials were transported to help rebuild Warsaw. During this time, some Polish organizations that had existed in the region before the war were reactivated.

After the fall of communism, many changes took place. Nowiny Raciborskie returned and remains the leading local newspaper to this day. Racibórz became the first European city to receive an Environmental Management certification. Today, the city is a local cultural hub and an important historical center of Upper Silesia, boasting numerous historical landmarks.

Oko na Świat © Artur Gołębiowski