All you need to know about the city of

CIESZYN

Poland – the Czech republic

Sightseeing

Numerous attractions make Cieszyn the perfect city for a weekend getaway. It’s worth taking a stroll through the picturesque Cieszyn Venice, discovering the legend of Three Brothers' Well, and visiting Rotunda of St. Nicholas, which is featured on the Polish banknote.

Curiosities

Cieszyn offers a whole range of regional legends and traditions, from the mysterious cursed arcades to unique local rifles.

History

Cieszyn is the capital of the entire historical region known as Cieszyn Silesia. But how did the fate of this fascinating city unfold, and why are there two Cieszyns today?

CONTENTS

History

- The Legend of the Cieszyn's Foundation

- The Medieval Heart of the City

- The Birth of the Duchy of Cieszyn

- The Grand Diplomacy of a Small Duchy

- When Swedes Marched into Cieszyn

- Cieszyn on the Imperial Route

- Cieszyn's Awakening on the Eve of the Great War

- A City Torn in Two

- Under Nazi and Communist Rule

SIGHTSEEING

Saint Nicholas Rotunda in Cieszyn

Admission: Rotunda only: 8 PLN; Piast Tower included: 12 PLN (regular), 8 PLN (reduced)

One of the most important, if not the most important, buildings in Cieszyn is Saint Nicholas Rotunda. Located on Castle Hill, it is the oldest building in the city, dating back to the 11th century. Moreover, it is the only Romanesque rotunda in Poland that has been preserved with its original nave vault (the roof over the area where the congregation sits). This monument is significant not only for historical reasons but also for its religious importance. Among other things, this is why it was commemorated on the Polish 20-zloty banknote.

Cieszyn Castle

Admission: Free

Built by the Habsburgs in the 19th century in a neoclassical style, the castle stands on the ruins of the former Piast castle. Estimates suggest that the original castle might have been even larger than Wawel Castle in Cracow. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in the 17th century, and only Piast Tower, St. Nicholas Rotunda, and a few fragments of the walls have survived from the old structure.

Today, the Habsburg castle houses a music school, while part of the building is used by a small hotel. The remaining section serves as a cultural institution, hosting various events. Regardless of the attractiveness of local exhibitions, the castle itself is also worth seeing, even if only from the outside.

Piast Tower

Admission (includes St. Nicholas Rotunda): 12 PLN (regular), 8 PLN (reduced)

Like St. Nicholas Rotunda, the Piast Tower is located on Castle Hill. It is the only one of the four towers built in the 14th century that has survived to this day. The tower was once part of Piast Castle, which was destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century. Although the tower itself was also damaged during the battles, it was later restored. Today, it serves primarily as a viewpoint, offering a panoramic view of the city.

Wall Remnants

Admission: Free

Although the old castle in Cieszyn was destroyed, some remains can still be seen. Besides the famous structures, fragments of the castle walls have survived and can be found near Cieszyn Museum. Close to Three Brothers’ Well, there is also the Mill Gate, which dates back to the same period. It was a passage connecting the town with a nearby mill.

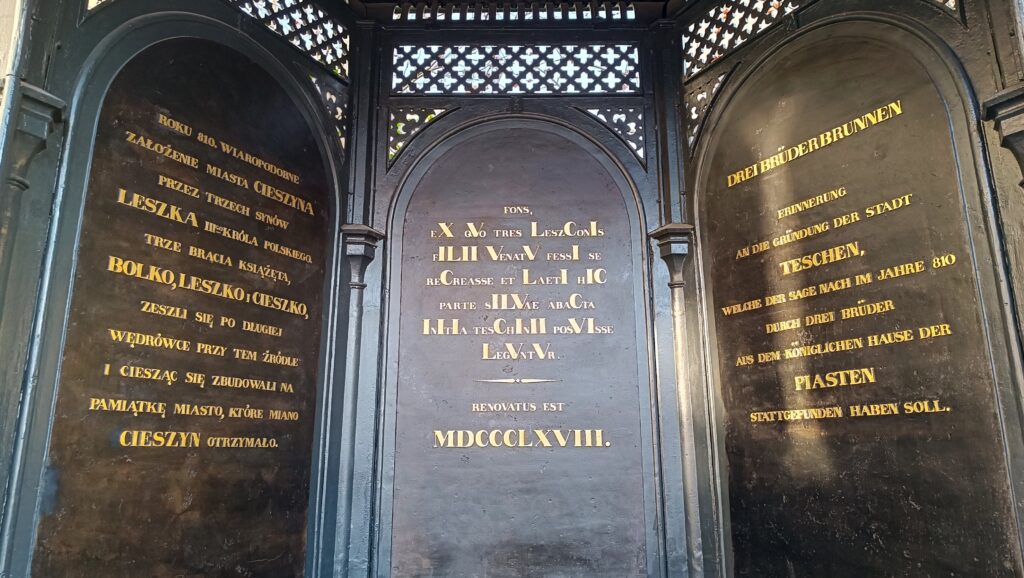

Three Brothers' Well

Admission: Free

This is an interesting symbol of the city, located not far from the center. The well itself existed as early as the 16th century, but its hexagonal structure and railings were only added in the 19th century. It has undergone multiple renovations, the most recent in 2023. Its name and decorations refer to the legend of Cieszyn’s founding, which is inscribed in Polish, Latin, and German.

In the year 810, the probable founding of Cieszyn by the sons of Leszek III, King of Poland. Three princely brothers—Bolko, Leszko, and Cieszko—met at this spring after a long journey. Rejoicing in their reunion, they built a city in memory of this moment, naming it Cieszyn.

Museum of Cieszyn Silesia

Admission: 30 PLN (regular), 20 PLN (reduced)

The oldest museum in Silesia, founded in 1802. Visits are only possible with a guide, and tours start on the hour. The tour lasts about an hour, though it may take slightly longer. The museum showcases not only artifacts related to Cieszyn but also items connected to various historical figures from Europe, including a desk that once belonged to Napoleon. Additionally, it houses the famous Cieszyn rifles—known as Cieszynki. The building also features a museum café, located in a former stable.

Market Square

Admission: Free

Cieszyn’s Market Square was established at the end of the 15th century. Most of the surrounding buildings date back to the 16th and 17th centuries. It is the central part of the city and also home to the town hall. Various events take place here, including the Christmas market.

Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene

Admission: Free

Nearby, you can also find the Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary Magdalene, the oldest church in the city. Its origins date back to the 13th century when it belonged to the Dominican order. The church also served as a burial site for former Piast princes and, at times, for local nobility. It was rebuilt in the 18th century after a fire, which gave it its present appearance.

Cieszyn Venice

Admission: Free

A part of the old town, popular for its artificial canal with numerous small bridges leading to houses, reminiscent of Venetian architecture. In the past, this district was primarily inhabited by craftsmen who needed constant access to water. Today, it remains a charming, though somewhat neglected, part of the city that attracts tourists with its unique atmosphere.

Archducal Castle Brewery Cieszyn

Admission: 50 PLN, 70 PLN with extended tasting

Founded in 1846 during the Habsburg era, the Archducal Castle Brewery is the longest continuously operating brewery in Poland. The tour lasts between 75 and 90 minutes and includes a tasting session. Advance reservation is required.

Czech Cieszyn

Admission: Free

Czech Cieszyn is the former western part of the city, now functioning as a separate administrative entity. It was historically the newer, industrial section, home to factories rather than historical landmarks. However, that doesn’t mean it’s not worth a visit!

The central part of the city is Czechoslovak Army Square, where you’ll find the Town Hall, built in the early 20th century. Another highlight is the charming 19th-century railway station, which is much older than its Polish counterpart. If you want to learn more about the city, a great place to visit is the Museum of the Cieszyn Region, which houses numerous exhibits and tells the history of the entire area.

CURIOSITIES

The Students’ Nightmare

It turns out that Cieszyn had its own cursed place—known as the Devil’s Arcades. At the intersection of Głęboka and Władysław Olszak streets, there once stood a building with arcades that, according to legend, brought bad luck. It was said that anyone who walked through them would experience misfortune before the day ended. Students, in particular, avoided the spot, believing that passing under the arcades would lead to bad grades. The place had such a terrible reputation that in 1912, during renovations, the arcades were completely removed. Was it just a legend, or was there some truth to the superstition? We may never know.

A Piece of Cieszyn in Your Wallet

Being featured on a Polish banknote is such an honor that it’s worth mentioning again. The St. Nicholas Rotunda, one of the oldest buildings in Poland (dating back to the 11th century) and the only surviving Romanesque structure with its nave vault intact, was placed on the front of the 20-zloty banknote. Alongside it, the banknote also features a coin from the reign of Bolesław the Brave and the famous Gniezno Doors.

War, Death, and a Mysterious Flower

If you’re interested in plants, you may have heard of Cieszyn Sneezeweed (Hacquetia epipactis). This unusual plant naturally grows in countries such as Italy, Croatia, and Slovenia. And yet, it can also be found in Silesia, including the Cieszyn region. How did it get there? The answer lies in an old legend.

During the Thirty Years’ War, Cieszyn was occupied by the Swedes. One of them, a young soldier named Ethelrad, struggled to cope with the hardships of war. One day, wounded and exhausted, he collapsed by the roadside. A local Cieszyn family found him and gave him food and water. Sadly, Ethelrad was dying, and his final wish was for soil from a small pouch he carried to be scattered over his grave. It was soil from his homeland—Sweden.

The family honored his wish. Additionally, they planted flowers on his grave, but they quickly withered. All winter, the grave remained barren, but in the spring, a new, extraordinary plant appeared. It covered the entire burial site of the Swedish soldier and, due to its blooming season, was named Cieszyn Sneezeweed.

A Sweet Heritage

One of Cieszyn’s most cherished traditions is baking Christmas cookies. This custom dates back to the Habsburg era and has survived to this day. Dozens of different types of cookies are made, featuring ingredients such as nuts, fruit, and butter. Each year, a baking competition is held, where anyone can participate. During the holiday season, these traditional Cieszyn cookies can be purchased, though their price can reach several dozen zlotys per box. This unique tradition offers a perfect opportunity to experience the region through its flavors!

From Cieszyn to the White House

Few people know that in the 14th century, Cieszyn was known not only in the local region but across Europe. This was thanks to Przemysław I Noszak, Duke of Cieszyn. Though he did not possess vast lands or a powerful army, he had something even more valuable—high-ranking friends. Przemysław was a vassal of Charles IV, King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, and soon became one of his most trusted allies, often entrusted with important missions.

One such mission arose when Charles IV’s daughter was to marry the King of England. Przemysław was responsible for safely escorting her across Germany and enemy-held France. He took his own daughter, Małgorzata, with him on the long journey. Upon arriving in England, Małgorzata met a local baron, Simon Felbrigg, and they eventually married. She settled in England, and years later, after the discovery of the Americas, her descendants emigrated. As a result, today, we can find the descendants of the Piast dynasty in the United States. One of the most notable examples? Former U.S. President Joe Biden.

The Bandit and the Golden Eggs

The Cieszyn Silesia region was often visited by bandits and outlaws, but none became as legendary as Ondraszek. He was remembered as an enemy of the nobility, yet folk tales portray him in a positive light. One such story goes as follows:

At the Old Market in Cieszyn, a beggar once asked a vendor for a broken egg, which she couldn’t sell anyway. She loudly refused, humiliating the man. Then, Ondraszek and his gang arrived. He asked for three eggs and cracked them into a cup. With each broken shell, a coin clinked inside. He announced that the eggs contained gold. Greedy, the vendor started smashing all her eggs, hoping to find more gold—but there was none. Ondraszek had secretly dropped coins into the cup. Having destroyed all her goods, the embarrassed woman ran away, while the outlaw gifted the beggar a few gold coins.

Even when a bounty was placed on his head, local peasants refused to turn him in. Eventually, he was killed by one of his own men, who struck him down with an axe. Though he died in 1715, songs and stories about the legendary outlaw are still created to this day. In his honor, one of Poland’s Intercity trains bears his name.

The Dying Tradition of Cieszyn's Rifles

A unique part of Cieszyn’s heritage is the production of light rifles known as Cieszynki. Their manufacturing dates back to the 16th century. Cieszynki were often richly decorated with gold, silver, mother-of-pearl, or ivory and were mainly used for bird hunting due to their small caliber. Today, these rifles are prized collector’s items, with prices reaching up to 500,000 PLN.

The craft of making such firearms is called gunsmithing, and as it happens, Cieszyn is home to the last gunsmith in Europe who still produces these extraordinary rifles.

HISTORY

The Legend of the Cieszyn's Foundation

Somewhere in Poland, at the beginning of the 9th century, King Leszek ruled over his stronghold. He had three sons: Bolek, Leszek, and Cieszek. One night, as he gazed at the sky, he noticed three stars shining in the west. He associated them with his sons and wondered if it was a sign from the gods. The next morning, he made a decision—he ordered his sons to set off in different directions within the kingdom, following the stars, and return only when the leaves began to fall from the trees.

The obedient sons followed their father’s command and went their separate ways with their retinues. When the autumn arrived, they considered their mission complete and wanted to return home. However, the fate had it that they all met at a spring with crystal-clear water. They decided that the area was so beautiful that they would build a new settlement there. Thus, in the year 810, the city of Cieszyn was founded—at least according to legend.

The Medieval Heart of the City

In reality, settlement in the region developed around Castle Hill, which is now in the center of Cieszyn. The area had been inhabited since the 9th century, and by the late 10th and early 11th centuries, it had become a castellany within the Piast state. This status meant the presence of a fortified stronghold that played an important military role in defending the borders. In the 11th century, the famous Rotunda of St. Nicholas was built in Cieszyn, making it one of the oldest Christian temples in Poland.

The Birth of the Duchy of Cieszyn

In 1138, Poland entered a period of feudal fragmentation and decentralization of power. In simple terms, this meant that local princes gained increasing independence and, in some cases, even complete sovereignty. By the late 12th century, Cieszyn became part of the Duchy of Racibórz, which in 1202 merged with the Duchy of Opole, forming the largest Silesian duchy in history. It was during this time that Cieszyn received its first municipal rights.

The city gained independence in 1290 when the ruling duke divided his lands among his sons. This marked the birth of the independent Duchy of Cieszyn. Immediately, efforts began to transform the stronghold into a castle to strengthen the city’s position. To this day, remnants of its walls can be found on Castle Hill. The Piast Tower also dates back to this period.

The Grand Diplomacy of a Small Duchy

In 1327, the Piast rulers of Cieszyn paid homage to the King of Bohemia, making the duchy a semi-dependent state. In 1374, the city was given Magdeburg rights, allowing it to develop trade and host market fairs, which effectively granted it full city privileges. In 1416, a series of rights and privileges were also granted to the townspeople.

The late 14th and early 15th centuries saw the political rise of the Duchy of Cieszyn. At that time, Przemysław I Noszak came to power. Thanks to his close ties with the King of Bohemia—who was also the Holy Roman Emperor—he became one of the most influential figures on the European political scene. As an imperial diplomat, he was responsible for negotiating treaties with other powers.

He was also granted the prestigious title of imperial vicar, meaning that upon the emperor’s death, he would share temporary rule over the empire until a new ruler was chosen. In the absence of the King of Bohemia in Prague, he served as the temporary governor of the kingdom. This was the peak of political influence for the Duchy of Cieszyn.

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, the region experienced significant growth. A land court was established to resolve disputes, the city expanded, and the market square was relocated to its current location. At that time, Cieszyn had 262 houses and a population of about 2,000.

When the Swedes Marched into Cieszyn…

A major event in the 16th century was the transition to Protestantism. Both the rulers and the townspeople embraced the new faith. The Dominicans’ gardens were confiscated and turned into public land, which was later developed and became an area known today as the New Town. However, subsequent rulers converted back to Catholicism, while the majority of the population remained Protestant.

In the 17th century, the Thirty Years’ War—a religious conflict between Catholic Habsburgs and Protestant states of Germany and Scandinavia—devastated much of Europe, and Cieszyn was no exception. The city suffered heavily from the presence of passing armies.

Between 1626 and 1627, Danish troops occupied the area, followed by the Swedish army in the 1640s, which seized the city in 1645. Financial troubles, waves of epidemics, and famine further ruined the city. To expel the Swedes, Austrian forces completely destroyed the Piast Castle.

To make matters worse, the last member of the Piast dynasty in Cieszyn, Duchess Elisabeth Lucretia, died during this period. According to the 1327 agreement, the duchy was supposed to become part of the Kingdom of Bohemia. However, since the Habsburgs had taken control of Bohemia, the city ultimately fell under Austrian rule. The Habsburgs would bear the title of “Duke of Cieszyn” until 1918.

Cieszyn on the Imperial Route

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the city faced a crisis. On one hand, war took its toll, and on the other, emigration played a significant role. The Austrian rulers, deeply committed to Catholicism, imposed various repressive measures on non-Catholics. As a result, many Protestants left Cieszyn. Economic recovery came only at the end of the 18th century with the construction of the so-called Imperial Road, which connected Vienna with Cieszyn, Kraków, and Lviv. The road was built as part of Austria’s strategy following the First Partition of Poland, which incorporated Kraków and Lviv into the Habsburg Empire.

Cieszyn began to flourish again, hosting international trade fairs as early as 1775. In 1802, the city established its first public library and Austria’s oldest museum. However, another difficult period soon followed—this time due to the Napoleonic Wars. After the fall of Vienna, Cieszyn briefly became the capital of the Habsburg state, as the imperial family fled there. Following Napoleon’s defeat, the city saw a revival of social life, with new cafés and various cultural associations emerging.

Cieszyn's Awakening on the Eve of the Great War

In 1846, the Archducal Brewery was founded in Cieszyn, a business that continues to operate in Poland to this day. Major changes arrived in 1848 during the revolutionary period known as the Springtime of Nations, when people across Europe rose against monarchies, demanding political reforms and greater autonomy for national minorities.

In Austria, these events led to the loosening of government control. Cieszyn’s residents gained the right to elect local authorities, local newspapers were established, and the city experienced an economic boom. Over the next 60 years, its population more than doubled. Cieszyn expanded rapidly, with new hotels for tourists, theaters, museums, and even a railway station. One of the city’s greatest achievements was the launch of a tram line in 1911.

Many social and cultural organizations thrived, with Poles playing a significant role in shaping the city’s identity. Notable institutions included the Polish People’s Reading Society, the Savings and Loan Association, and the National School Association of the Duchy of Cieszyn. Polish educational institutions were also established, including a high school and a primary school. Although estimates of the Polish population in Cieszyn ranged from 34% to 60%, they were the largest ethnic group. Their growing national consciousness soon found an opportunity for realization—with the outbreak of World War I.

A City Torn in Two

World War I disrupted the European order, and Cieszyn played a significant role as the headquarters of the Austro-Hungarian army between 1914 and 1917. However, Austria lost the war, and the collapse of the empire led to the redrawing of national borders. Many nations regained independence, which sparked territorial disputes across Central Europe.

Cieszyn, once a Czech fief but primarily inhabited by Poles, became a subject of contention. Initially, plans were made to divide the city based on the ethnic composition of its residents. However, in 1920, Poland was at war with Soviet Russia, and Czechoslovakia took advantage of the situation by pressing for a border arrangement that favored its claims.

As a result, the more industrialized part of Cieszyn was granted to Czechoslovakia. Additionally, many German residents left the city. These changes slowed Cieszyn’s economic growth, which only began to recover in the mid-1930s. Meanwhile, a significant Polish minority remained in Czech Cieszyn.

Under Nazi and Communist Rule

In 1938, Poland annexed Zaolzie, reunifying Cieszyn. Citizenship was granted only to those born in the region before World War I, and Czech institutions were dissolved. However, just a year later, Nazi Germany launched its full-scale invasion of Poland. Cieszyn fell without resistance. The Germans took control of all key positions in the city, while Poles and Czechs faced discrimination. Many were executed in public killings, and the Jewish population was deported to concentration camps. Despite these horrors, the city itself remained relatively undamaged.

After the war, Cieszyn was once again divided, and the new communist authorities took power. They banned independent organizations, confiscated church property, and nationalized businesses. Following the socialist vision, trade networks were state-controlled, and large-scale housing projects were initiated. Nevertheless, the city retained its cultural traditions, continuing to serve as an educational center.

The fall of communism restored Cieszyn’s local self-governance. The economy transitioned to capitalism, and cooperation with Czech Cieszyn flourished through joint cultural and civic projects. Today, despite its small size, Cieszyn remains an important cultural hub in the region.

Oko na Świat © Artur Gołębiowski